Apollo 13: The Successful Failure

2-11-2026 — Written by Kevin Jie

During the Space Race, the United States’ aerospace administration, NASA, created the Apollo program: a series of missions to space with the sole purpose of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely back to Earth.

The first few Apollo missions were tests to assess the capabilities of their rocket models while making adjustments and refinements according to the outcome of the test.

These few tests were designed to cover the wide variety of situations that the moon landing mission would eventually, or possibly, encounter.

Arguably the most important of these tests were Apollo 8 and Apollo 10. The primary goals of these missions were to perform and rehearse most of the orbital and spacecraft work that the following mission, Apollo 11, would have to do when they would attempt to land on the moon.

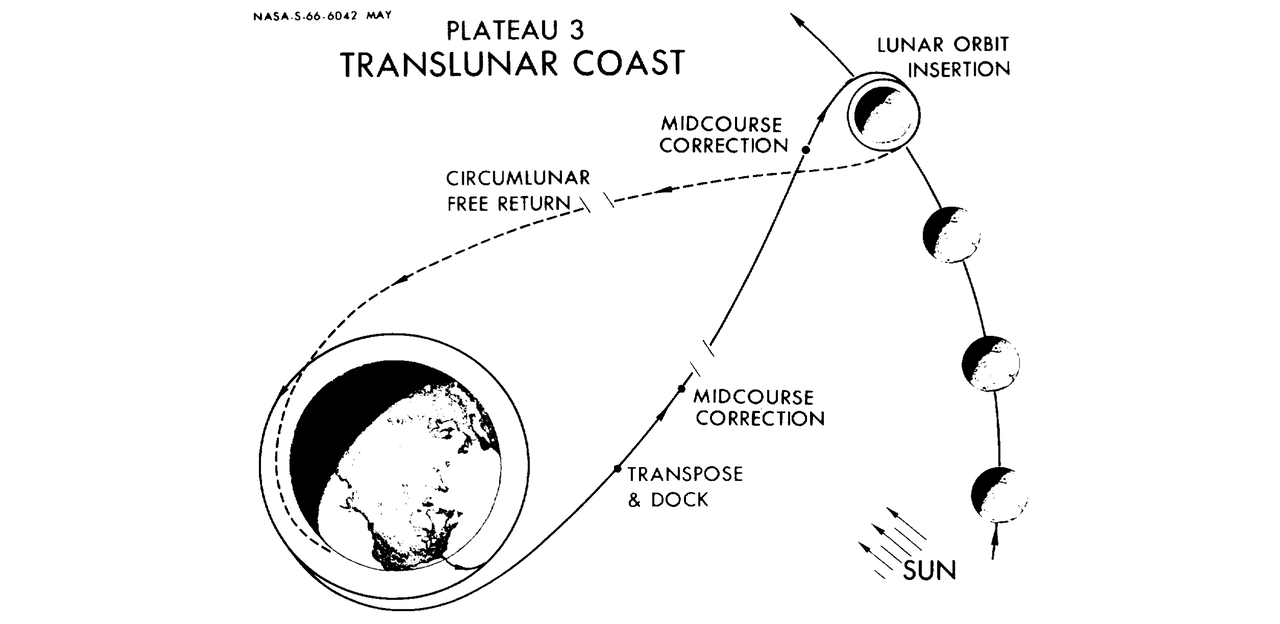

One of the tasks that Apollo 8 and Apollo 10 accomplished during their mission was the free-return trajectory (FRT).

This was an orbital path that allowed a spacecraft to swing from Earth to the moon and back without requiring additional forces to be applied.

The FRT was a path that was meant to be used during the astronauts’ transit to the moon, but in case of an emergency, the crew could just ride the trajectory back to Earth without the need of their engines.

Following the successful missions of Apollo 11 and 12, Apollo 13 was supposed to be the third mission to land men on the moon.

For the first 55 hours and 14 minutes of Apollo 13’s flight, everything happened as expected.

The crew at the time, 42-year old Jim Lovell, 38-year old Jack Swigert, and 36-year old Fred Haise, had just finished their mid-journey television transmission.

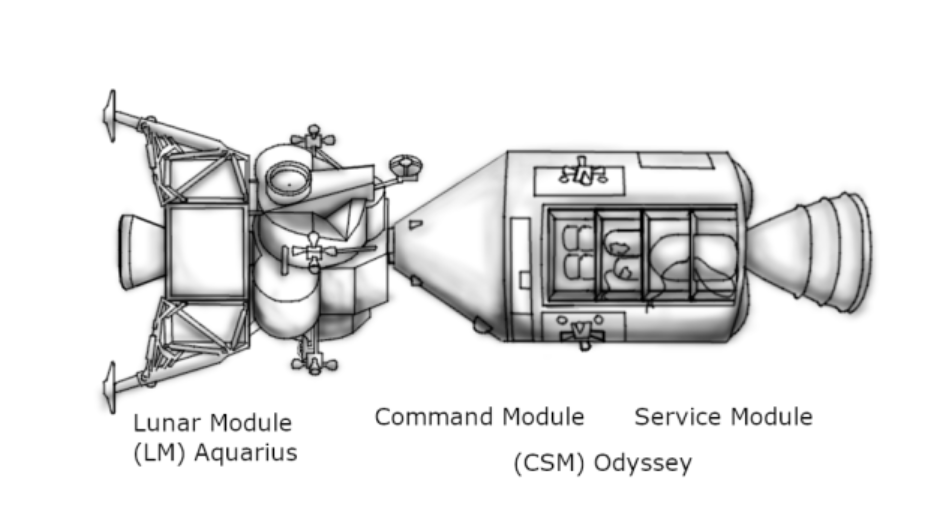

During this broadcast, the crew toured and explained different parts of the control module (CM) and lunar module (LM).

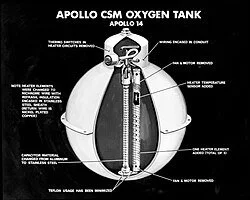

After the TV broadcast, mission control wanted the crew to perform a cryo stir in the oxygen tanks, a routine automated action that would stir the liquid oxygen, which usually stratifies, in order to provide more accurate readings on how much is remaining.

The crew proceeded with the request, however, when the switch was flipped, things went horribly wrong.

After the stir, oxygen tanks 1 and 2 began to fall into a worsening state; triggering a master caution warning.

Oxygen tank 1 dropped in pressure around two minutes after the warning before steadily decreasing in pressure.

However, oxygen tank 2 was almost the complete opposite of 1, rapidly rising and slightly dropping in pressure in sporadic intervals before completely going off-scale, indicating a failed sensor.

During all of this, the flow rates of liquid into the fuel cells seemed to have the same issues as Oxygen tank 2, except with accurate readings but erratic values.

Ultimately, the crew completely powered the CM down and evacuated to the LM in order to preserve the remaining power and fuel in the CM for reentry.

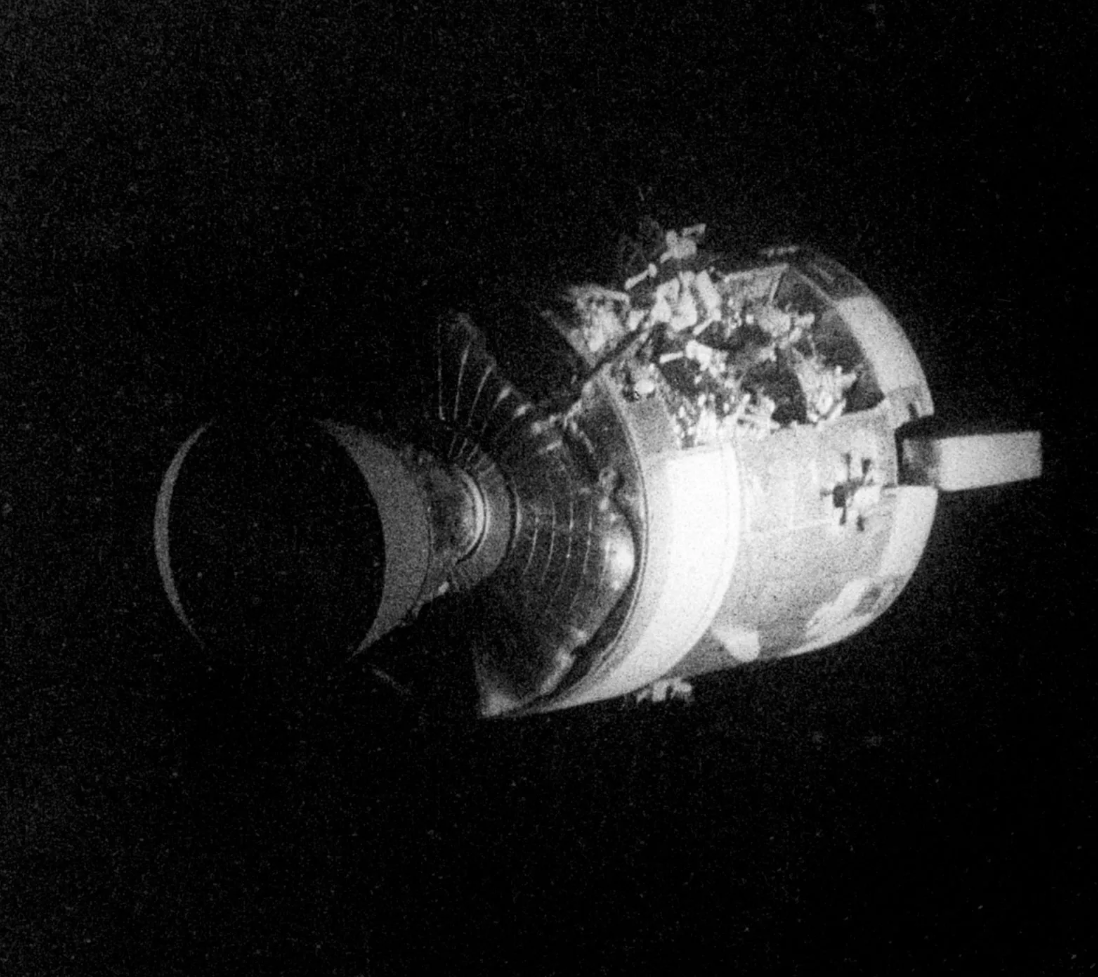

To describe the crew’s predicament in other words, an explosion occurred within an inaccessible part of the module that caused major damage to the interior of the SM and had caused the module to lose a significant amount of oxygen.

Around 57 hours and 11 minutes into the mission, it was known that they only had around 15 minutes of electricity left in the CM.

It was from here that they were told to go to the LM to get power. In the LM, CAPCOM spoke to Swigert, saying, “I have an activation procedure. I’d like you to copy it down.”

The procedure CAPCOM spoke of were the steps needed to shutdown the CM in order to preserve its batteries and cooling water, elements that would be used during reentry.

After these preliminaries were accomplished, it had been stated that Apollo 13 was a failed lunar landing, as they lacked the resources to land on the moon and make it back to Earth.

At around 93 hours and 30 minutes into the mission, carbon dioxide levels were rising.

The LM had a scrubbing system, but it was only built to handle two occupants.

This led to the slow buildup of carbon dioxide.

Even worse, the crew realized that the canisters used to remove the carbon dioxide wouldn’t last to reentry.

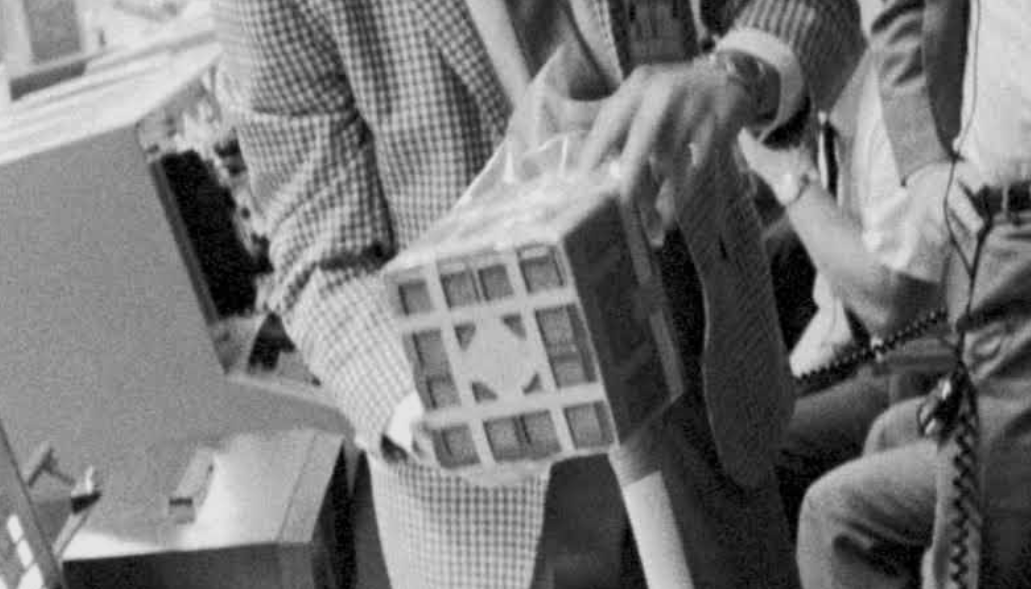

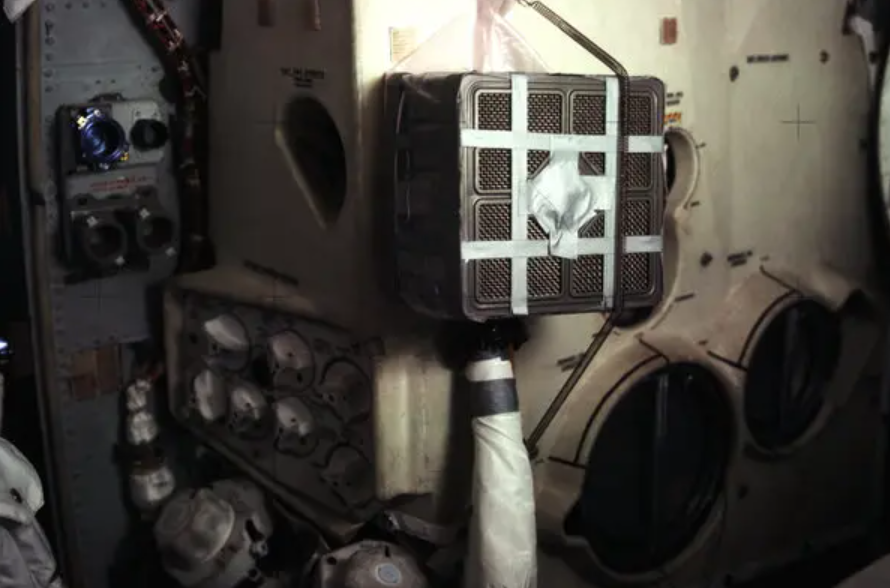

Immediately notifying mission control of the problem, it was up to the great minds at Houston to design a makeshift carbon dioxide remover that the astronauts could build with the materials they had aboard.

Within the following 35 hours, Houston had created one using cardstock spacesuit hoses, plastic bags, scrubbers from the CM, and duct tape.

This single fix ended up saving the lives of the astronauts and allowed them to proceed with their transit back to Earth.

The mission would conclude 142 hours after lift off, marking the successful return of the Apollo 13 crew.

Although the mission was a failure, it’s usually referred to as a successful failure.

No, they did not accomplish the mission they sought to complete, but they managed to live through what could’ve been death.

Apollo 13 will forever stand as a sobering reminder that trouble continues to lurk in space, and that the lack of danger doesn’t mean the guarantee of safety.